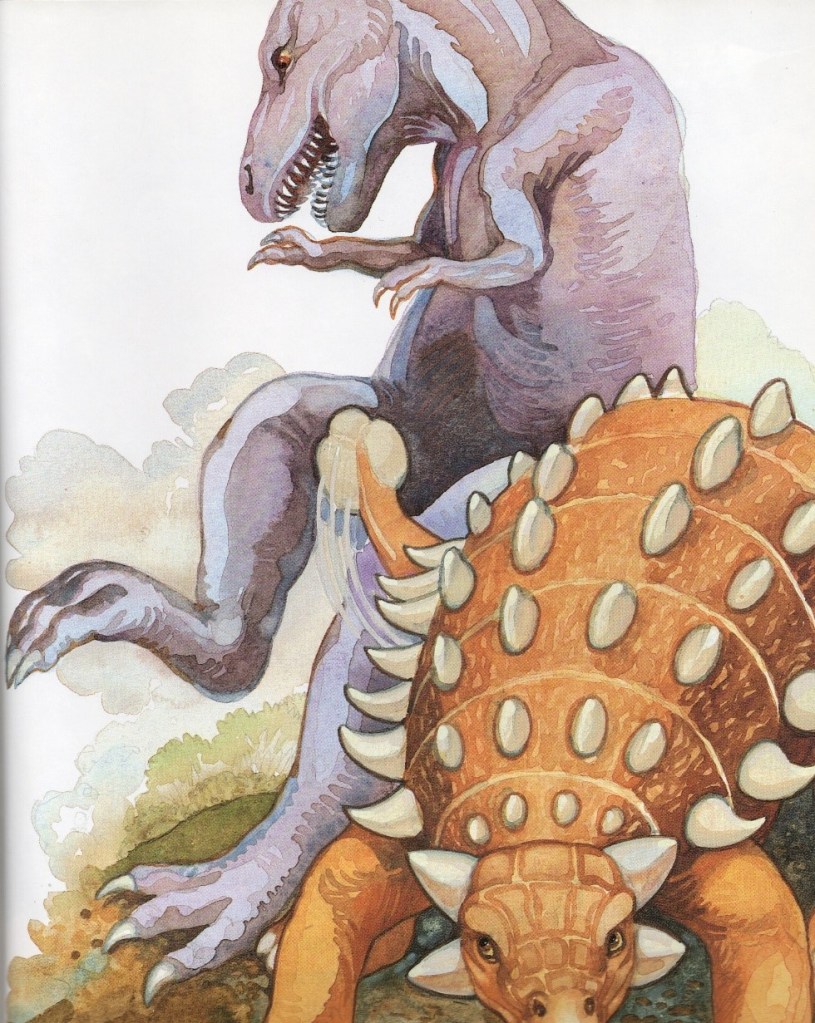

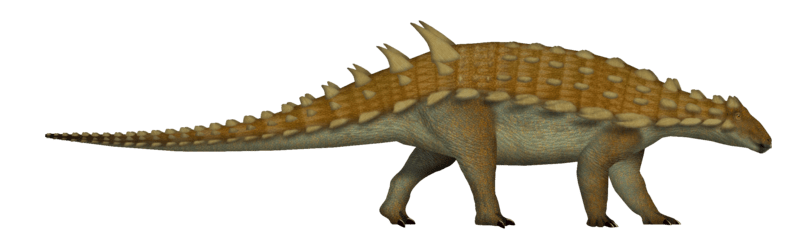

If a plant eater didn’t want to become dinner, it had to be able to defend itself. Some plant eaters were very good at this. They had sharp claws or horns of their own. But one type of dinosaur didn’t need to fight back. All it had to do was squat down. This was the Ankylosaurus (an-KI-luh-sawr-us). The Ankylosaurus had thick, bony armor over almost all of its body.

The Ankylosaurus was a huge dinosaur. That alone would have been enough to discourage most meat eaters. It was just a little smaller than a bus – about 26 feet long and 7 feet tall, weighing as much as five tons. But it didn’t look like a bus – it looked like a tank.

Tanks are covered with metal armor. The Ankylosaurus’ armor was made from thick bands or plates of bone. Spikes and knobs were scattered across the back and over the head. The armor covered its back, neck, and head – even its eyelids!

Tim Evanson, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The armor was probably very frustrating to a hungry meat eater. Even if a meat eater could dodge the knobs and spikes, all it would get was a mouthful of bony armor – and maybe a few broken teeth.

A meat eater had only one chance. The belly of the Ankylosaurus didn’t have any armor. If the meat eater could get to that soft spot, it could still have an Ankylosaurus snack. But all the Ankylosaurus had to do was crouch to the ground, folding its legs underneath. That way the only parts a meat eater could get to were covered with armor.

Some meat eaters probably tried to flip it on it back. If it were flipped over, the weight of its armor would prevent it from flipping back, much like a turtle. It would be completely helpless. However, trying to flip an Ankylosaurus was like trying to flip a tank. Most ankylosaurs were much too heavy for even the strongest meat eater to budge. And, of course, it was hard to find a place to grab on, with all those spikes and knobs in the way.

If a meat eater kept on bothering an Ankylosaurus, it ran the risk of provoking the creature into an attack. At the end of its tail, the Ankylosaurus had a huge, bony club. The club was about 16 inches wide and made of solid bone. The muscles in the tail were very strong. If an Ankylosaurus swung its club hard enough, it could probably have knocked down any other dinosaur, even a Tyrannosaurus. It might have been able to break a meat eater’s leg – or its skull – with that club. It certainly would have made that meat eater very sorry it ever wanted an Ankylosaurus for dinner!

Ankylosaurus had some trouble finding its own dinner. It was hard for it to move its head and neck because of all that armor. And it certainly couldn’t rear up on its back legs with all that heavy bone to lift. That meant that it could only feed on plants that grew close to the ground. Maybe that wasn’t all bad, though. Every now and then it might scoop up some ants or a few beetles for a tasty dessert.

You might think that the Ankylosaurus with its heavy armor was a slow-moving dinosaur, but it was more like a rhinoceros than a turtle. A rhinoceros is very large and heavy, but it can run fast. Ankylosaurus wasn’t as fast as a rhino, but it could run as fast as 6 mph, which is about as fast as most people can run. The powerful leg muscles of Ankylosaurus helped it to move quickly if it needed to.

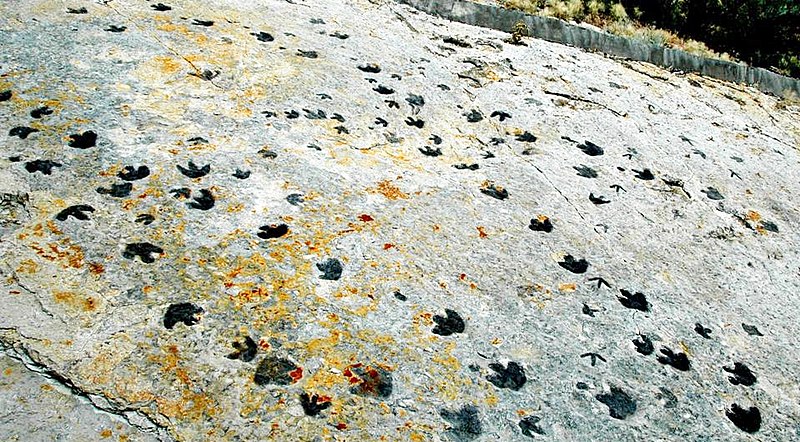

Ankylosaurus was the biggest armored dinosaur that we know, but it was not the only one. It had many relatives. Some had more spikes. Some had few or none at all. Some had tail clubs. Some did not.

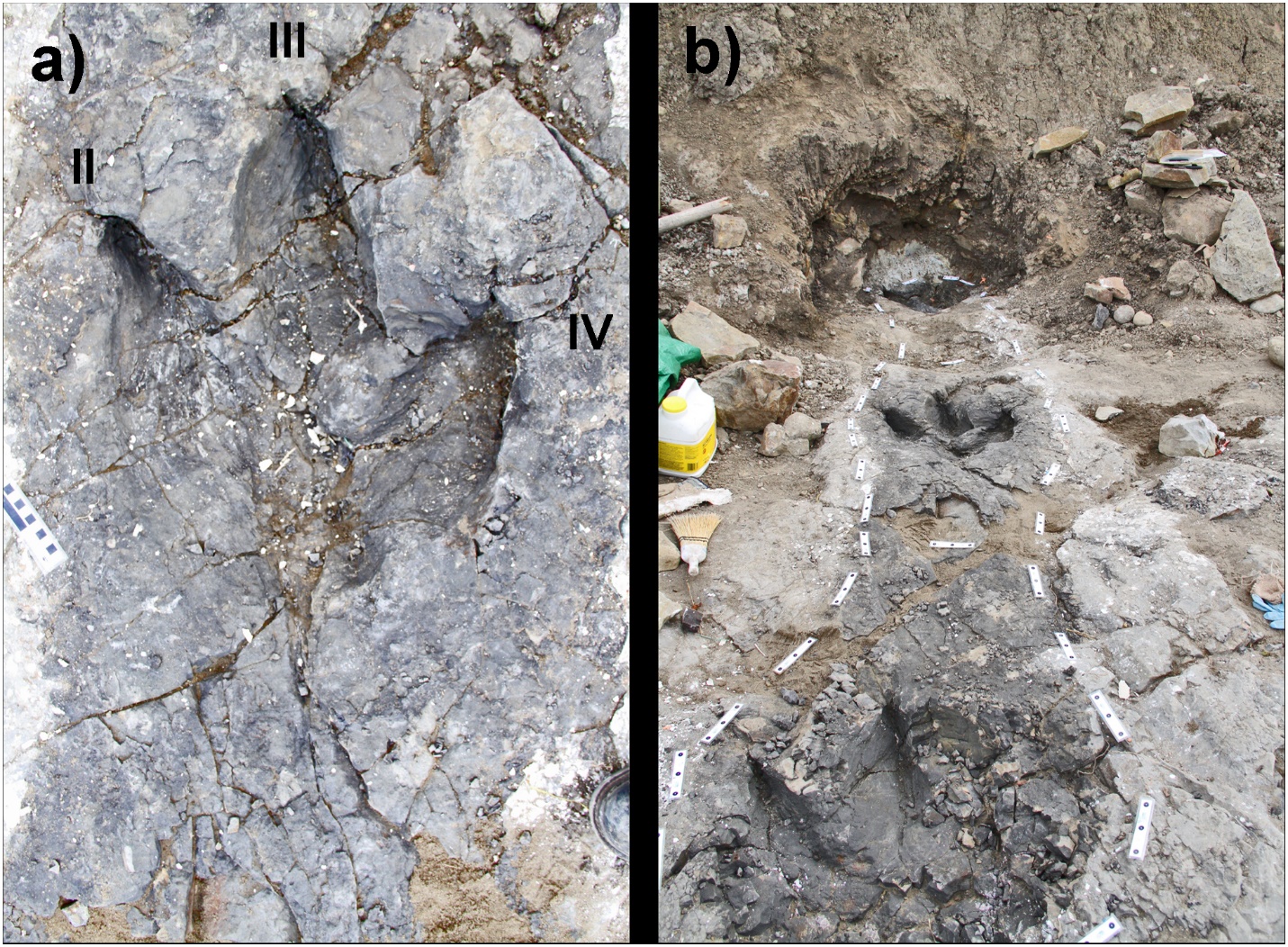

UnexpectedDinoLesson, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Xi Yao, Paul M Barrett, Lei Yang, Xing Xu, Shundong Bi, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

But most of them were good at surviving. Many of the armored dinosaurs lived until the very end of the age of dinosaurs. It wasn’t easy living in the same world as Tyrannosaurus, but it could be done – by a walking tank!

Sources (Click Me!)

“Ankylosaurus.” Natural History Museum of London. n.d. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/ discover/dino-directory/ankylosaurus.html

“Cretaceous Insects.” Western Australian Museum. n.d. https://museum.wa.gov.au/ explore/dinosaur-discovery/cretaceous-insects

Norman, David. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Crescent Books, 1985.

Rasmussen, Patty and Talon Homer. “Ankylosaurus: A Tank-like Herbivore With a Killer Club Tail.” How Stuff Works. 10 July 2024. https://animals.howstuffworks.com/ dinosaurs/ankylosaurus.htm?utm_source=facebook&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=hsw-owned&utm_content=animals&fbclid=IwY2xjawFYdItleHRuA2Flb QIxMQABHSJZrzMY8s_ckpGF7a0h_hX_66x-bgLwyX_Zqb-4gJSO4DdqauNWL6RUmA_aem_vUroiI23KZyLQ6TE2xysxw

Riehecky, Janet. Ankylosaurus. The Child’s World, 1991.