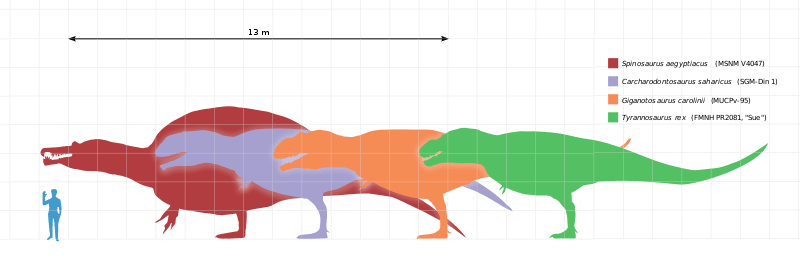

As I wrote a few weeks ago, there are some serious contenders for Tyrannosaurus’ crown as the biggest, fiercest land carnivore of all time. Giganotosaurus and Megaraptor could certainly give Tyrannosaurus a battle, but this week’s contenders, from Africa, are even more powerful.

Carcharodontosaurus (Kar-KAR-oh-don-toe-SAWR-us) lived in Northern Africa during the late Cretaceous Period 99 to 94 million years ago. Its name means “shark-toothed lizard,” and its long jagged-edged teeth are much like those of a shark.

Most estimates rank Carcharodontosaurus as about three or four feet longer than Tyrannosaurus. It’s hard to tell because scientists have found only some tens of bones and a number of teeth from it.

Even if Carcharodontosaurus is slightly larger, Tyrannosaurus still has a number of advantages. Smithsonian Magazine reported that Tyrannosaurus’ bite force was almost 12,800 pounds, stronger than any other animal that ever walked on land. (Megalodon, an enormous extinct shark, does have it beat at 41,000 pounds. There was also an extinct crocodile named Purussaurus which had a bite of 15,500 pounds of force.) Tyrannosaurus’ bite was stronger than the force of an average-sized African elephant dropping on you. (I don’t want to even think what that means about Megalodon’s bite.) Tyrannosaurus’ teeth are shaped like bananas. The rounded shape is very effective at breaking bones. Carcharodontosaurus’ teeth were shaped differently. They were thinner, more like the blade of a knife. They were meant for shearing meat from bones. They might have broken if Carcharodontosaurus bit directly into thick bones.

Tyrannosaurus also had an advantage in eyesight. Its eyes were more forward looking than Carcharodontosaurus’. This gave Tyrannosaurus a wider range of sight, enabling it to see more of what was in front of it. Because of the shape of Carcharodontosaurus’ skull, it would have had to drop its head toward its chest to see any distance ahead. This likely meant it hunted its prey by ambushing them, rather than chasing after them. Regardless, if the two had ever met, it would have been a titanic battle.

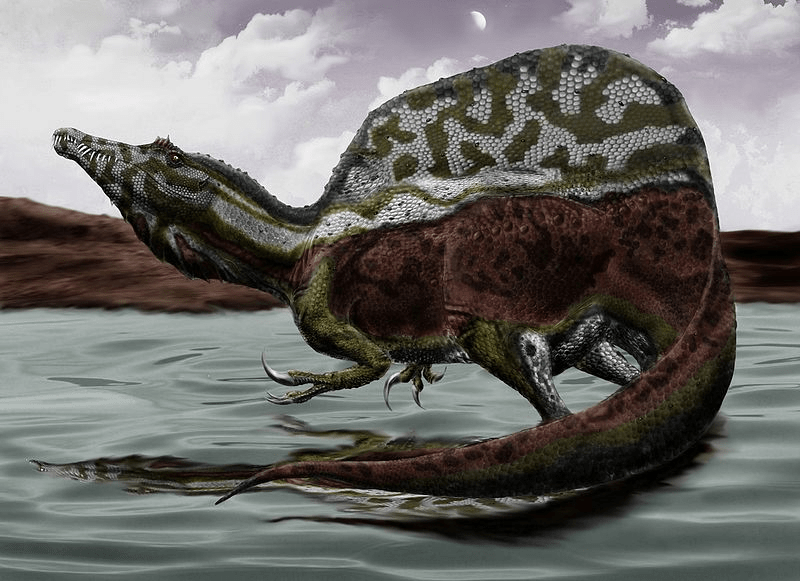

And then there’s the biggest of the top five, Spinosaurus. It also lived during the late Cretaceous Period and was found in North Africa. This creature was about 49 feet long and weighed just over eight tons. However, its back legs were much shorter than Tyrannosaurus’, making it about 9 feet tall at the hip compared to Tyrannosaurus’ 12-15 feet in height. However, if the sail on Spinosaurus’ back is included, then it was 15-16 feet tall.

It’s difficult to compare its power to the other three because it was shaped differently and lived a different kind of life. It was a little thinner, with a large sail on its back, a paddle-shaped tail and its jaws were long and narrow like a crocodiles’. Its teeth were like overturned ice cream cones instead of curved with jagged edges. Scientists think that it hunted at least part of the time in the water and that on land it stayed near the coast and ambushed its prey, rather than running it down. Its likely that, despite its huge size, its shorter legs would have made it less agile than Tyrannosaurus. Its tail would have been a formidable weapon for knocking other dinosaurs around, but that might not be enough.

Figure 1 (left) Spinosaurus tooth – 1 Jiří X. Doležal (about me), CC BY-SA 3.0, via via Wikimedia Commons. Figure 2 (right) Tyrannosaurus tooth

Scientists don’t know which of these dinosaurs was most powerful. Even though it’s been many years since Giganotosaurus, Megaraptor, Carcharodonotosaurus, and Spinosaurus were discovered, scientists still know very little about them. It takes a long time for fossil bones to be excavated and studied. For me, however, Tyrannosaurus still holds its crown by virtue of its long teeth, large brain, and powerful bite. But never forget that there is another alternative: any day a paleontologist might dig up a new dinosaur that could take on all of them.

What do you think?

Sources (Click Me!)

Aureliano Tito, Aline M. Ghilardi, Edson Guilherme, Jonas P. Souza-Filho, Mauro Cavalcanti, and Douglas Riff . “Morphometry, Bite-Force, and Paleobiology of the Late Miocene Caiman Purussaurus brasiliensis.” PLOS ONE. 17 Feb. 2015. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0117944.

Black, Riley. “The Tyrannosaurus Rex’s Dangerous and Deadly Bite.” Smithsonian Magazine. Oct., 2012. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/the-tyrannosaurus-rexs-dangerous-and-deadly-bite-37252918/

Currie, Philip J and Colleayn O. Mastin. The Newest and Coolest Dinosaurs. Grasshopper Books Publishing, 1998.

Gasparini, Zulma, Leonardo Salgado, and Rodolfo A. Coria (eds.). Patagonian Mesozoic Reptiles. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2007.

Hecht, Jeff. “Contenders for the crown.” Earth 7.1 (Feb. 1998): 16. _Academic Search Premier_. EBSCO. Judson University Library, Elgin, IL.15 July 2009 <http://www.judsonu.edu:2048/login?url=htto://<http://www.judsonu.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=89601&site=ehost-live>.

Horner, John R. and Don Lessem. The Complete T-rex. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993.

Larson, Peter and Kenneth Carpenter. Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Tyrant King. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2008.

Monastersky, R. “New beast usurps T. rex as king carnivore.” Science News 148.13 (23 Sep. 1995): 199. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Judson University Library, Elgin, IL. 15 July 2009 <http://www.judsonu.edu:2048/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=9510094855&site=ehost-live>.

Novas, Fernando, E., Diego Pol Juan I. Canale; Juan D. Porfiri; Jorge O. Calvo. “A bizarre Cretaceous theropod dinosaur from patagonia and theevolution of Gondwanan deomaeosaurids. Proceedings: Biological Sciences, Mar2009, Vol. 276 Issue 1659, p1101-1107, 7p.

Rafferty, John P. “Megalodon.” Britannica. <https://www.britannica.com/animal/megalodon>.

Richardson, Hazel. Smithsonian Handbooks: Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Life. New York: Dorling Kindersley, 2003.

Sereno PC, Myhrvold N, Henderson DM, Fish FE, Vidal D, Baumgart SL, Keillor TM, Formoso KK, Conroy LL. “Spinosaurus is Not an Aquatic Dinosaur.” Elife. 2022 Nov 30;11:e80092. doi: 10.7554/eLife.80092. PMID: 36448670; PMCID: PMC9711522.

Smith, Nathan D., Peter J. Makovicky1, Federico L. Agnolin, Martin D. Ezcurra, Diego F. Pais3 and Steven W. Salisbury. “A Megaraptor -like theropod (Dinosauria: Tetanurae) in Australia: support for faunal exchange across eastern and western Gondwana in the Mid-Cretaceous.” Proceedings of the Royal Society. 20 May 2008.

“Spinosaurus.” Natural History Museum of London. nd. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/dino-directory/spinosaurus.html

“Spinosaurus aegyptiacus.” The Sauropodomorph’s Lair. 23 Aug. 2020. <https://thesauropodomorphlair.wordpress.com/skeletal-reconstructions/dinosaurs/theropoda/spinosaurus-aegyptiacus/>

Spotts, Peter N. “Giant dinosaur fossil forces scientists to question theories.” Christian Science Monitor 03 Dec. 1997: 3. Academic Search Premier. EBSCO. Judson University Library, Elgin, IL. 15 July 2009. <http://www.judsonu.edu:2048/login? url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=9712050418&site=ehost-live>.

Stevens, Kent A. “Binocular vision in theropod dinosaurs.” Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 12 June 2006. 26 (2): 321–330. doi:10.1671/0272-4634. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1671/0272-4634%282006%2926%5B321%3ABVITD%5D2.0.CO%3B2.

Straight, Will. “Carcharodontosaurus vs. Tyrannosaurus.” 2015. https://www.dinosaurhome.com/carcharodontosaurus-vs-tyrannosaurus-685.html

“Sue at the Field Museum.” The Field Museum, Chicago, IL. 2007. 15 July 2009.

University of Queensland. “Australian Dinosaur Found To Have South American Heritage.” ScienceDaily 15 June 2008. 10 September 2009 <http://www.sciencedaily.com /releases/2008/06/080613111410.htm>.