At first it was just disappointment. Thirty-year-old graduate student, Robert dePalma, was excavating a fossil site on a ranch in North Dakota. When he began digging in 2021, he had hoped to find layers of sediment that would show the years leading up to the end of the Cretaceous Time Period. The site was a large area, covering about two acres and measuring about three-feet deep, but it was clear the entire layer had been laid down all at once by some kind of flood. There were fish fossils, but they broke apart into tiny flakes when he tried to dig them out.

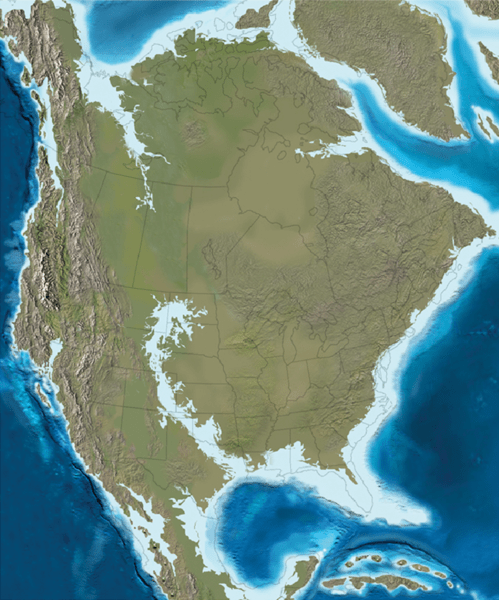

Ron Blakely, Colorado Plateau Geosystems is credited for the maps, in the paper, and Terry A. Gates et al are stated to be the copyright holders for the paper and its contents, CC BY 1.0, via Wikimedia Commons

He continued to dig, though, and he found tiny, white/gray bits that looked like sand. When he looked at them under a magnifying glass, he recognized their tear-drop shape as belonging to microtektites. Tektites, as mentioned in last week’s blog, are created when rock becomes so hot that it turns to liquid. They can be formed by volcanos or by an asteroid hitting the earth. The liquid rock is flung into the air in small bits until it goes high enough the air cools them. As they fall to Earth, they form tear-shaped, glass fragments. Over millions of years, they turn to clay. The tektites he found were so small they were classified as microtektites. DePalma found millions of them. He knew the bed he was digging in was from the end of the Cretaceous Time Period. It dawned on him that the microtektites might be from the asteroid that hit the Earth then.

DePalma continued his excavation. He found an amazing number of fossils. Most of the time fossils are flat, crushed by layers and layers of rock, laid down over time. But many of these fossils were three-dimensional because they had been deposited and covered immediately, and the sediment around them acted as support.

He found new species of fish and a variety of plants, including tree trunks smeared in amber. The amber contained what appeared to be asteroid debris. He suspected that the site he was working on had been formed the very day the asteroid hit! If that was true, it was an incredible find!

NASA Goddard Photo and Video, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As a child and young adult, dePalma had collected bones and fossils. He lent them to a nearby museum where he also reconstructed some dinosaur skeletons. But when the museum went bankrupt, they refused to return his collection. After that he was very careful about the fossils he excavated. In the United States, fossils belong to whoever’s property they are found on and can be sold to anyone. It is not unusual for a paleontologist or commercial fossil collector to sign a contract with a private land owner for an excavation. They usually agree to split the profit on any fossils that are found and sold. Museums and universities don’t like this arrangement because important finds can disappear into private collections.

Realizing that this site was potentially one of the most important ever found, he entered a long-term agreement with the ranch owner. The details of the agreement have been kept private.

Over the next several years, dePalma continued to excavate. He confided in only three other people what he had found, including Walter Alvarez, the man who had originally proposed the asteroid theory. DePalma did publish a paper that described a hadrosaur bone he’d found with a tyrannosaur tooth embedded in it. The bone had healed, indicating that the hadrosaur had gotten away after the attack, which dePalma said proved Tyrannosaurus hunted live prey. Scientists have long debated whether Tyrannosaurus was just a scavenger who lived by finding meals that were already dead or if it hunted live prey. DePalma’s evidence was not taken very seriously because he was just a student and a commercial fossil collector.

Continued excavation at the site revealed a paddlefish, but underneath it was a mosasaur tooth. A paddlefish is a freshwater fish, but a mosasaur is a giant, saltwater reptile. How could fossils of both be in the same site? DePalma and the others tried to come up with a theory to explain this, but they couldn’t.

Raver Duane, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Nobu Tamura email:nobu.tamura@yahoo.com http://spinops.blogspot.com/, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Then he found small impact craters, about three inches across. At the bottom of each crater was a normal-sized tektite. DePalma was sure they had to be from the asteroid that ended the Cretaceous Period, even though the impact site was about 2000 miles away. He arranged to have a laboratory compare the tektites to material from the Chicxulub (CHICKS-ih-lube) Crater. They matched! The asteroid impact was so explosive that debris was thrown 2000 miles away!

For years dePalma had worked on the site in secret, sharing it with just a few others. But in 2019, he invited a reporter from New Yorker magazine to see the site and tell the world its story. When the story was published, the scientific community was skeptical. The normal procedure for announcing a significant discovery would be to submit a paper to a peer-reviewed journal where experts would evaluate the evidence before it was published, not submit it to a literary magazine. Many scientists disparaged his theories because dePalma was just a student only working on a PhD, a nobody who dug up fossils to sell rather than to study. But they sold dePalma short, as evidence he was right continued to pour in. (And he did eventually publish papers in peer-reviewed journals.)

YellowPanda2001, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

DePalma has named the site Tanis, after an ancient Egyptian city. In the late Cretaceous, a large inland sea stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to what is now the U.S./Canadian border. What is now North Dakota was subtropical. DePalma and the people he has now working with him on the site have determined that Tanis was a sandbar located between a river and a forest. They think that when the asteroid hit in the Gulf of Mexico, it created a gigantic earthquake. It took maybe ten minutes for the shock waves to reach Tanis. The disturbance caused giant waves to form on the inland sea shown in the map above. They flung sea creatures, such as the mosasaur, at Tanis, many miles away. In addition, waves were formed in the nearby river, flinging freshwater creatures onto the site. DePalma found a turtle that was flung so hard that a tree branch went right through its body.

Continued excavation has also revealed

- Fish with asteroid debris clogging their gills,

- Ant nests with the ants still in them and asteroid debris in their tunnels,

- Large feathers that likely came from a large dinosaur,

- Broken bits from almost all the dinosaurs known to have lived in that area during the late Cretaceous,

- A small burrow inhabited by a small mammal,

- Dinosaur eggs and hatchlings,

- Pterosaur bones,

- A partial mummified Thescelosaurus with its skin still intact,

- And pieces of the actual asteroid preserved in amber.

Nobu Tamura (http://spinops.blogspot.com), CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

DePalma and his crew continue to work on the site. It will take years to explore it thoroughly. Right now, though, it’s an amazing picture of what happened the day the dinosaurs died.

Death of the Dinosaurs: Part 2

Death of the Dinosaurs: Part 1

Sources (Click Me!)

Barras, Colin. “Astonishment, Skepticism Greet Fossils Claimed to Record Dinosaur-Killing Asteroid Impact.” Science. 1 April 2019. https://www.science.org/content/article/astonishment-skepticism-greet-fossils-claimed-record-dinosaur-killing-asteroid-impact

Black, Riley. “Fossil Site May Capture the Dinosaur-Killing Impact, but It’s Only the Beginning of the Story.” Smithsonian Magazine. 3 April 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/fossil-site-captures-dinosaur-killing-impact-its-only-beginning-story-180971868/

Hunt, Katie. “Fragment of the Asteroid That Killed Off the Dinosaurs May Have Been Found.” CNN. 11 May 2022. https://www.cnn.com/2022/05/11/world/dinosaur-apocalypse-tanis-fossil-site-scn/index.html

Preston, Douglas. “The Day the Dinosaurs Died.” New Yorker. 29 March 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/04/08/the-day-the-dinosaurs-died