Dinosaurs left behind skeletons, eggs, footprints, even fossilized poop. All these things help us imagine what the world of the dinosaurs looked like. But we really don’t have much of an idea what it sounded like. We can be pretty sure that the dinosaurs’ world echoed with the thud of gigantic feet, the splash of water, and the buzz of insects. But did dinosaurs bark, howl, grunt or growl? We don’t know.

However, scientists do think that one dinosaur “played a horn.” That dinosaur was Parasaurolophus (par-uh-sore-oh-loaf-us). Scientists have made models of the long, hollow crest on its head, and when they blew air through it, it made a deep, low tone, like a musical instrument.

This link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QtpSOpUDCb8 will help showcase what Parasaurolophus might have sounded like.

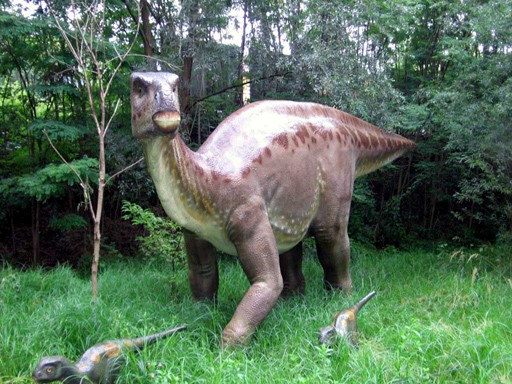

The crest of Parasaurolophus was a very long, thin tube of bone. It began at the dinosaur’s nose and stretched up way above its head. On some Parasaurolophus the crest reached six feet long – longer than most people! This crest was hollow inside. A tube for air went up from each nostril to the tip of the crest and then curved back down like a trombone. All the air it breathed had to make that long journey. Not even Pinocchio had a nose that long!

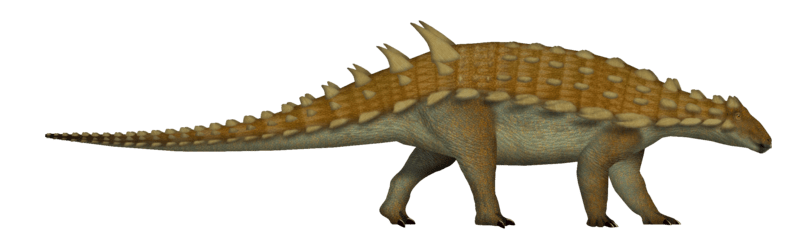

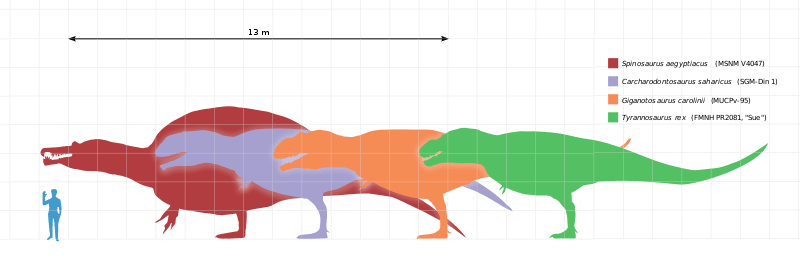

In every other way Parasaurolophus was ordinary. It was one of the plant eaters nicknamed “duckbilled” because its mouth was long and flat like a duck’s bill. It stood on two strong back legs, with shorter front legs that it could also walk on or use as arms. It was about 30 feet long and 16 feet tall, and it probably weighed 3 or 4 tons. This was about the size of a bus – or an average dinosaur.

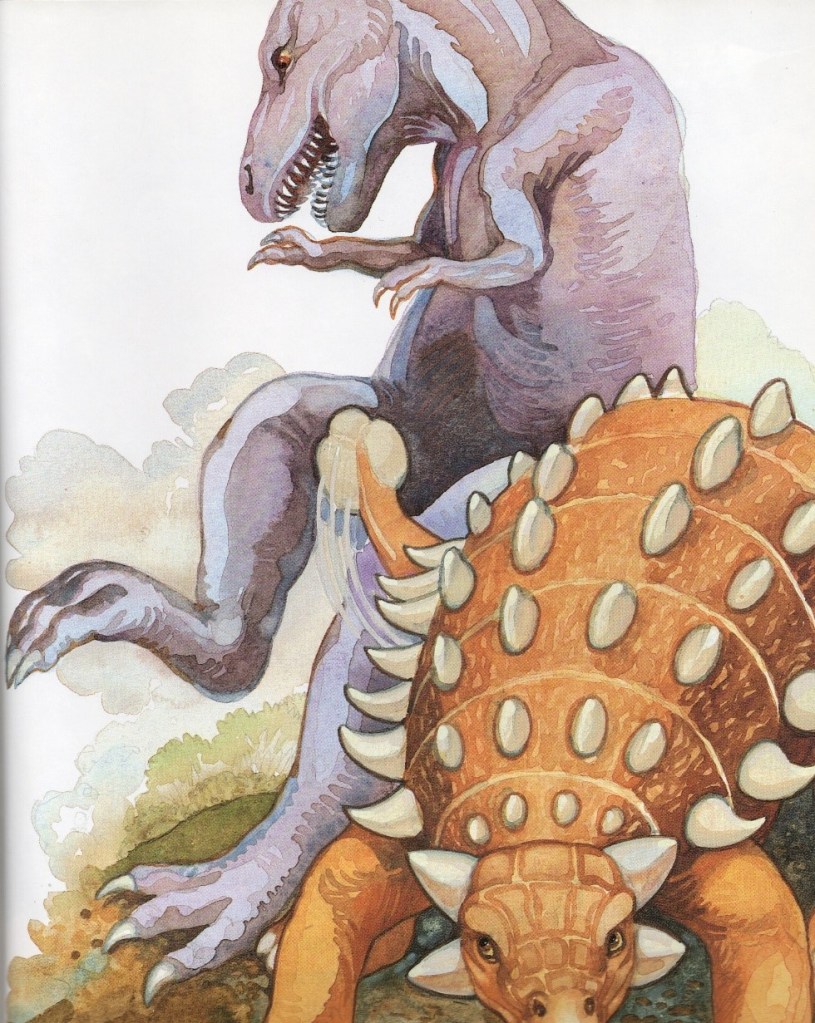

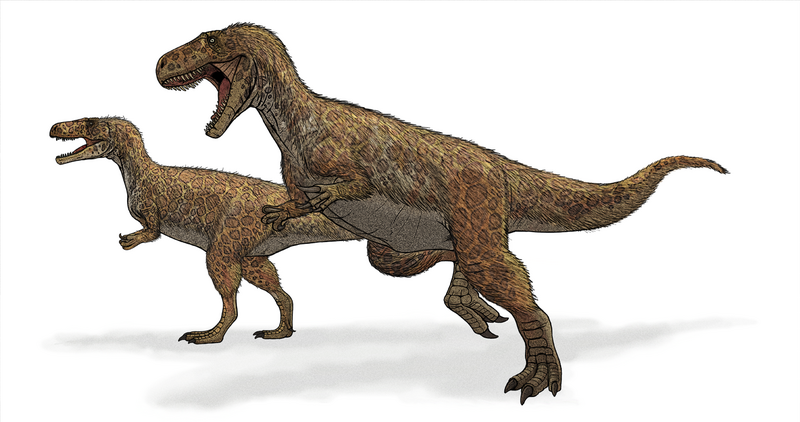

Parasaurolophus might have used the sounds it could make with its crest to communicate different messages, such as danger or food ahead. A herd might have honked at a Tyrannosaurus to go away. A special kind of honk might have attracted a mate.

Parasaurolophus also might have used its crest to push away branches in a thick forest. The cassowary, a large flightless Australian bird, uses its crest for that today. Another idea is that the crest brought cool air close to the Parasaurolophus’ brain to keep it from getting too hot. And it might have been able to smell through it, so it could seek out its favorite plants or tell when a meat eater was close by.

Scientists don’t know for sure if the Parasaurolophus used its crest in any of these ways. They continue to look for clues and ideas.

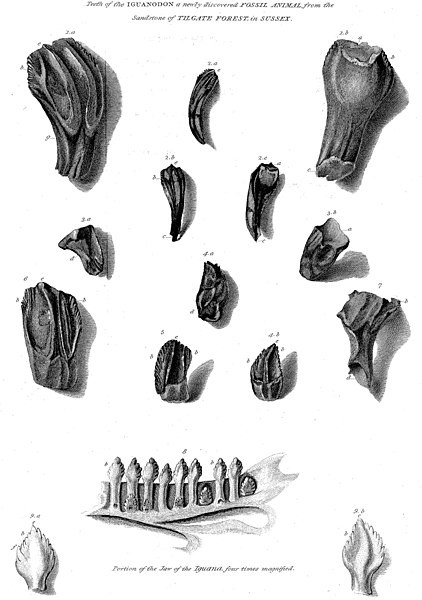

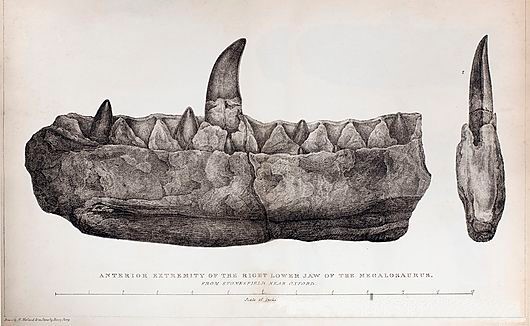

Scientists do know that Parasaurolophus had strong jaws which would be good for eating tough plants, such as pine needles, leaves, and different fruits and seeds. Its cheeks were loaded with good teeth for grinding things up. It even had three or four extra teeth above the ones that showed. That way if any of its teeth broke or wore out, new ones moved down. A Parasaurolophus may have grown more than 10,000 teeth during its lifetime.

Parasaurolophus lived right up to the end of the age of dinosaurs, outliving the other known duckbilled dinosaurs. But sixty-six million years ago, the last dinosaurs on earth died, including Parasaurolophus. Never again will the world echo with the sound of those gigantic feet or the honk of a Parasaurolophus calling to its friends.

Sources (Click Me!)

Norman, David. The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs. Crescent Books, 1985.

“Parasaurolophus.” Natural History Museum of London. https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/dino-directory/parasaurolophus.html

“The Real Parasaurolophus.” Philip J. Currie Dinosaur Museum. 2024. https://dinomuseum.ca/2021/01/the-real-parasaurolophus

Riehecky, Janet. Parasaurolophus. The Child’s World, 1990.