Everybody knows where you find mummies – in pyramids in Egypt. But not always. People made the Egyptian mummies, but under just the right conditions, Mother Nature can make them, too. A few, very rare dinosaur mummies have been found. Not just a skeleton but a fossil with skin and soft tissue preserved.

To become a mummy, a dinosaur that died would first need to be protected somehow from predators, so they couldn’t tear it apart. That could happen in a number of ways. The dinosaur could die in a place away from predators or be covered over with water from a flood or a giant mudslide. Some could be covered by the collapse of a sand dune.

Being away from predators isn’t enough. Minerals need to soak into the skin and soft tissue before they have a chance to decay. It helps if the dinosaur is covered with something that slows down the microbes that cause that decay, such as certain kinds of mud. It also helps to have the right kind of skin. Some scientists have suggested that the reason most of the dinosaur mummies that have been found are duckbilled dinosaurs is that there was something in their skin that slowed down decay, giving the skin time to fossilize.

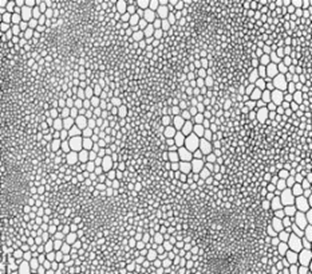

The first dinosaur mummy was found in Wyoming in 1908. It was an Edmontosaurus (ed-MON-to-SAWR-us), a duckbill dinosaur common in the late Cretaceous. Though it’s hard to see in this picture, almost 2/3 of the body is still covered with skin. The skin consists of very small scales, less than two tenths of an inch in diameter. Unlike those of many reptiles, the scales are more like separate bumps than overlapping scales.

Different sizes are clustered together. The scales on the upper side of the body are larger than those on the lower side. Soft tissue between the claws on its hands suggests that it had padded feet, and tissue above the spine suggests it had a soft ridge along the back of the neck and spine.

Several other duckbill dinosaur mummies were found during the 1900s, but they didn’t have as much preserved soft tissue or skin. The next dinosaur mummy of any importance was not found until 2000 when scientists in Montana unearthed a Brachylophosaurus (BRACK-uh-LOF-o-SAWR-us), which is another type of duckbilled dinosaur. They named it Leonardo (nearby graffiti from 1916 said that Leonard loved Geneva). This mummy was 90% complete and revealed that the neck had unusually strong muscles and that its skin was scaly, similar to Edmontosaurus. Scientists were able to examine the contents of its stomach. It ate leaves, conifers, ferns, and flowering plants like magnolias. Its stomach also revealed parasites – small bristly worms.

Probably the most spectacular dinosaur mummy of all was discovered in 2011 in Alberta, Canada. It is Borealopelta (BORE-e-AL-o-PEL-ta), not a duckbilled dinosaur but a nodosaur, an armored dinosaur. In life it was 18 feet long and weighed about 3000 pounds. The back legs and tail are missing, but what is there is amazing. The skin was so well preserved that scientists were able to use a mass spectrometer to find out what the color of the dinosaur was.

The back and sides of the dinosaur were a dark reddish brown, while the belly was a lighter reddish brown. We see that pattern of coloring, ark on top and light underneath, in many animals today. It helps those animals hide from predators. Not only was the skin well preserved, but also the armor itself. Usually, the armor falls off armored dinosaurs before they fossilize. Sometimes pieces of armor are found nearby, but often they aren’t. This mummy shows exactly where and how every piece of armor was attached. In addition, scientists have learned that the spikes were covered with keratin, the same stuff that fingernails are made of. This made the armor look bigger: the better to scare away predators – or perhaps to attract a mate.

No doubt additional exciting dinosaur mummies will be found in the future. A potential one, discovered in Montana in 2014, still lies encased in a 35,000-pound block of stone, waiting to be dug out. Each mummy helps fill in gaps in our knowledge of how dinosaurs looked and behaved.

Which do you like better? Egyptian mummies or dinosaur mummies? Let me know in the comment section below.

Sources (Click Me)

Brachylophosaurus. Wikipedia. 22 March 2021, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Brachylophosaurus#cite_note-MTT06-7

“Dinosaur Mummies.” Fossil Wiki. Fandom. n.d. https://fossil.fandom.com/wiki/ Dinosaur_mummies#Discovery_and_analysis

“Fossil ‘Mummy’ Shows Glimpse of Dinosaur Skin.” American Museum of Natural History.

28 April, 2017, https://www.amnh.org/explore/news-blogs/news-posts/fossil-mummy-shows-glimpse-of-dinosaur-skin.

Greshko, Michael. “The Amazing Dinosaur Found (Accidentally) by Miners in Canada.” National Geographic. June 2017. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/magazine/ article/dinosaur-nodosaur-fossil-discovery

“Nodosaur Dinosaur ‘Mummy’ Unveiled with Skin and Guts Intact.” All That’s Interesting. 19 June 2020, https://allthatsinteresting.com/nodosaur-dinosaur-mummy.

“Spectacularly Detailed Armored Dinosaur “Mummy” Makes Its Debut.” Smart News. Smithsonian Magazine. 2021. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/mummified-armored-dinosaur-makes-its-debut-1-180963311/